Is convenience even more fundamental to an enterprise than either efficiency or effectiveness?

That’s the curve-ball that Nick Gall threw to me, in a comment on my earlier post ‘Efficient versus effective‘.

It’s quite a long comment (and, unfortunately, quite a long reply here…), so I’ll split it up into its paragraphs and reply to each in turn.

Before we start, I’d best warn that this might at first seem just another exercise in Tom’s Pernicketily Pedantic Precision – yet I think (hope?) that by the end of it you’ll see why being so pernickety and pedantic has its very real payoffs…

It recently occurred to me that there is a something even more fundamental than either effectiveness and efficiency. It is convenience.

More fundamental? More common, perhaps, yes; but inherently of higher-priority than either efficiency or effectiveness? I have very real doubts about this… as I’ll explain as we go along.

Likewise, convenient in what sense? And for whom? Those are definitely non-trivial questions…

Think about it. If something is sufficiently convenient for someone, she will sacrifice large amounts of efficiency and effectiveness for the sake of such convenience. That’s why we as individuals and as communities are so wasteful. Look at “conveniences” like fast food, disposable anything, even convenience stores.

Yeah, I do think about it, a lot. Which is exactly why it worries me, a lot…

And which is also why the questions “Convenient in what sense? for whom?” become extremely important – especially for an architecture of the enterprise.

Think about it in turn: if creating wastefulness is a core driver for the entire enterprise, just how long do you think that enterprise is going to last within a broader closed-ecosystem? Short answer is, yeah, it’ll poison itself at some point, or just plain run out of resources, through lack of efficiency. Which means that it’s also ineffective, because it can’t keep on going – it can’t continue its success. In that sense, convenience cannot and must not be assigned a higher priority than efficiency or, especially, effectiveness.

If the inefficiency and wastefulness are low enough such that other not-actually-acknowledged parts of the ecosystem are able to deal with the wastes and replenish the renewable-resources, it can perhaps seem like the system could continue forever. Reality is that it’s in fact dependent on those not-actually-acknowledged components in the enterprise’s broader-ecosystem – which introduces very real and very dangerous risks for the enterprise.

Since the advent of consumerism, yes, ‘convenience’ has become a very common element in business-models and in many so-called ‘value-propositions‘. Yet when the business-model depends on creating wastefulness – as in ‘planned-obsolescence‘ and suchlike – the resultant increasing system-stresses and decreasing system-efficiencies put not just the business-model but the entire ecosystem at risk. As can be seen all too easily at your local garbage-mountain…

In systems-terms, it’s merely one example of what I’ve termed the ‘quick-profit failure-cycle’:

It’s a short-cut version of the real business-cycle that’s seemingly very profitable in the short-term, but suddenly drives itself into the ground, often apparently ‘without warning’, when its inefficiencies finally catch up. The only people who really ‘win’ from such a cycle are the scavengers – and even will they drive themselves into oblivion when the whole ecosystem becomes too poisoned for its survival. This isn’t a human-specific pattern, by the way: it applies at every level of ecosystem, including those in which (in principle) no human is involved at all.

People generally aren’t all that interested in making their own lives more efficient or more effective. It’s typically managers who want the people they manage to be effective and efficient. People generally just want things to be easier for themselves, i.e., more convenient, even if it means being less efficient or effective.

I fully agree that that’s what people want (or perhaps have been taught to want, or incited to want, in a consumerism-based economics and a ‘rights’-based political-model – which is not necessarily the same as what they actually want…).

Yet there are two fundamental distinctions here that we must not gloss over:

- want (desire) versus need (viability)

- local ‘efficiency’ versus whole-of-system effectiveness

Many current business-models, and consumerist-economics in general, exhort us to prioritise want over need, because doing so ensures that the need is (‘ideally’) never satisfied. Which drives the quick-profit failure-cycle ever-faster. Which creates more and more non-resolvable waste. Which threatens whole-of-system viability. Looks great in the short-term, but in reality not such a good idea…

Simple personal example: for my own viability, I need to manage my weight, and health in general. I’m fortunate in that I don’t drink or smoke, but I do tend to fall back on comfort-food when I’m stressed (which, like most people these days, I often am). Exercise is not convenient; watching my diet is not convenient; doing meditation or suchlike to manage the stress is not convenient. I don’t want to do any of those things at all. Reality, however, is that Type-2 diabetes would definitely not be convenient… and a heart-attack or stroke even less so. Oops…

To continue the example: I want to offload my responsibility for my own health to someone else: my doctor, for example. Or, ideally, just pop the right kind of pill, and all the problems magically go away. Reality is that it just don’t work like that: in fact that way addiction lies, in all manner of seriously-nasty forms. Again, not a good idea… What I need to do instead is to find a way in which I would want to take responsibility for my own health – which is a very different concern than simplistic notions of ‘convenience’.

In fact, exactly the same applies to the over-reliance, in business and elsewhere, on IT and ‘deus-ex-machina’ in general: it’s a desire for ‘control’ over things that are inherently ‘uncontrollable’, for ‘certainty’ where, by definition, no certainty can be had. It’s a desire for things to be ‘convenient’, not real-world messy: a desire that the machine can magically take away all the effort – particularly the real-world effort of dealing with real-world people and their real-world issues. That’s all that IT-centrism is: another addiction to another kind of ‘magic pill’. And like all addiction, it doesn’t work: it can sometimes give the illusion of satisfying the short-term want, but not the real need – especially not in the longer term.

And consider, again, local versus global (‘whole-system’) – because this is where ‘convenient for whom?’ really does come into the picture. Let’s use the old inside-out versus outside-in:

And again, let’s use Chris Potts’ dictum that “Customers do not appear in our process; we appear in their experiences”.

If, as the organisation, we seek convenience from our own perspective, looking inside-out, then yes, we want all of our customers to adapt themselves to fit our processes. That’s easy for us; most-efficient, for us. But is it convenient for the customer? Often, no: too often, very far from it, in fact.

If, as the customer, we seek convenience from our own perspective, looking outside-in, then yes, we want the company to adapt itself to our desires, our needs. That’s more convenient for us; easier for us; most-efficient, for us. But is the company going to be able to do that? Given the way most systems are still built, around silos and suchlike, this can be kinda tricky…

Each of those is locally ‘efficient’, from the perspective of a single stakeholder – but not necessarily so from the global perspective of the system as a whole. There are trade-offs here, often very complex trade-offs: and if we don’t get them right, across the whole system, then the system itself is at risk of becoming non-viable.

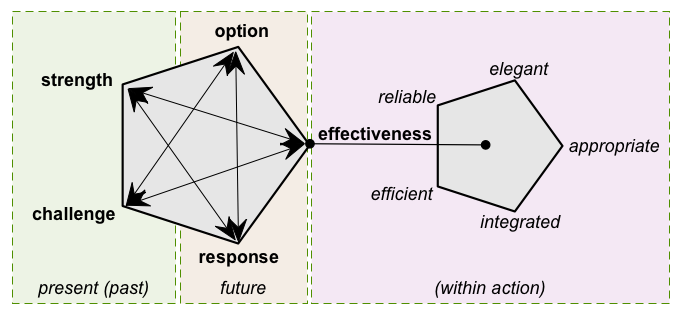

Simple illustration: if the customer’s experience is of inconvenience, then the organisation’s business-model is going to be at risk, because the customer won’t want to do business with that business. Likewise, if the organisation’s experience is that the customer is too inconvenient, then it won’t want that customer. Hence, yes, convenience is a factor here - but it’s not the only factor. Likewise, efficiency – minimum ‘waste’ from a single perspective – is a factor, but it’s not the only factor. And probably the simplest term that we have, to describe the complex melding and interaction of the relationships between all of those factors, is effectiveness. Which, in turn, I would summarise in terms of the interaction between themes such as efficient, reliable, integrated, elegant and appropriate (‘on purpose’), as illustrated in my old SCORE framework:

And the simplest way to summarise an enterprise is to describe it as an ‘ecosystem-with-purpose’ – there’s a real sense of purposiveness to an enterprise, which there usually isn’t in other types of ecosystems.

If there’s purpose, we’re going to need to be to identify when we’re ‘on-purpose’, and when we’re not. Which means that we need indicators for ‘on-purpose / not-on-purpose’. Otherwise known as success-metrics. Which, in turn, derive from the vision and values and derived-principles of the enterprise. Of which ‘convenience’, yes, may be one of those values. May. Not necessarily. Not always. Certainly not ‘the centre of everything’ – especially at the whole-of-enterprise level.

So we need to get our priorities really clear on this: convenience is, yes, often a desirable attribute of success – but it is not success itself. If we ever get this one the wrong way round, we’re in deep trouble…

Never underestimate the power of the path of least resistance. People prefer it to the most efficient path and the most effective path. The path of least resistance is actually quite a profound concept, underlying not only human behavior, but also evolution and physics. See also, principle of least effort and principle of least action. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Path_of_least_resistance

I don’t underestimate it, at all.

It’s probable that I most often see it as a problem – especially in business-models – and for all of the reasons I’ve outlined above.

And the reason I most often see it as a problem is that most people seem to underestimate the damage it can do, at a whole-of-context level, when they try to apply it both to and at too narrow a scope.

When ‘path of least resistance’ for one stakeholder-group ends up massively increasing the resistance elsewhere, we have a non-viable system. That’s exactly what causes ‘silo-wars’ and suchlike within organisations. And it also causes failure of business-models, when organisation-centricity, or even customer-centricity, demands that ‘least-resistance’ should apply only to itself, to the possible or even probable detriment of all other players.

Perhaps one of the nicest illustrations of this is the huge ‘special-case’ required to make a Penrose Triangle ‘impossible-object’ seem to make sense in the physical world. It ‘makes sense’ – provides least-resistance to ‘making-sense’ – from one viewpoint only (the right-hand photo in the images below), whereas from all other other viewpoints there may well be too much resistance against ever ‘making-sense’ at all:

In short, for an enterprise-architecture, the only way that works is that everywhere and nowhere is ‘the centre’, all at the same time. Which means that the ‘path of least resistance’ for the enterprise as a whole must be calculated from every ‘the centre’ in the enterprise – sometimes all at the same time.

Which, in most cases, will give very different results from a simplistic single-point calculation. Which, if we’re going to apply concepts such as ‘path of least resistance’ to any whole-of-enterprise architectures, is likely to be a rather important distinction…

BTW, It’s tempting use “expediency” instead of “convenience”. Then we could talk about the 3 E’s: efficiency, effectiveness, and expediency. Unfortunately, the latter has negative connotations.

Yep, ‘expediency’ does indeed have ‘negative connotations’. And, in this context, for very good reasons too – as I hope I’ve shown above.

Convenience and expediency may be useful attributes to the so-called ‘value-proposition’ for a business-model, which itself is a sub-component of one view within a business-architecture, which is arguably a component of a view of an enterprise-architecture from one player’s perspective. Don’t confuse a business-model with an enterprise-architecture: they’re not the same things at all…

To add one more point: expediency, or convenience, is actually from the perspective a single stakeholder. In that sense, it’s a sub-component – and an optional sub-component at that – of the broader theme that I’ve described in SCORE and elsewhere as ‘elegance’: the human-factors in a context. As in the SCORE diagram above, ‘elegance’ sits at the same level as ‘efficiency’ – yet both of those, in turn, are merely sub-components of overall effectiveness.

In other words, there’s a real hierarchy here that – if we want to protect viability of the system as a whole – should not be messed with or misunderstood:

- convenience is an optional sub-component of ‘elegance’

- ‘elegance’ is a (usually) non-optional component of effectiveness

- overall-effectiveness is always the core success-concern for any ecosystem and/or enterprise

In short, whilst convenience or expediency may well be relevant factors in an enterprise, do not attempt to place them at the same level as either efficiency or effectiveness. Doing so is really, really, really not a good idea… not wise at all.

Hence, also in short, don’t do it! ![]()

‘Nuff said on this for now, anyway: over to you, perhaps?